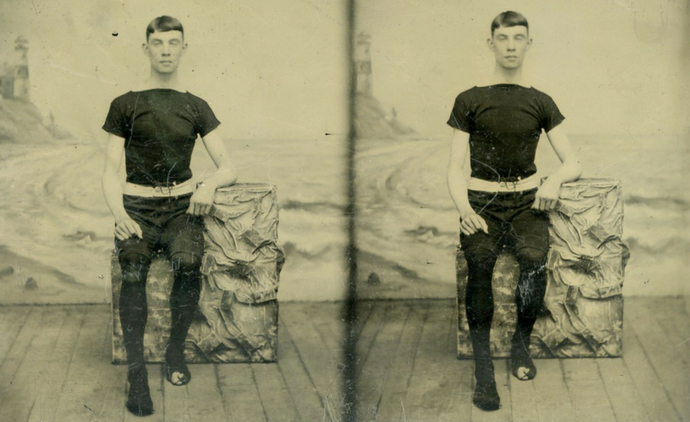

You’ve definitely seen a tintype photograph, maybe in a local antique shop or in a grandparent’s basement.The tintype process was first described in France in 1853, but then patented by Hamilton Smith in the U.S. It was a popular method of photography throughout the mid-to-late 1800’s. Due to its ease of printing production, tintype photography was utilized for a variety of photographic purposes like portraiture and the documentation of the American Civil War.

The reason for the using these underexposed images allowed pioneer photographers a shorter exposure time. This is a major reason why they are considered to be the “earliest Polaroid.” As prints themselves, they’re rather haunting and visually distinctive. These photographs also stand up to the centuries and are prized by archival experts.

Due to the development of similar yet higher quality techniques like albumen, tintype slowly became more of a novelty. To this day, many a local summer fair still offers this fun option– a unique style of photograph you might take at a booth with friends.

How Does the Tintype Process Work?

Tintypes (ferrotype, melainotype or wet plate photos) are made by making a direct positive on a sheet of iron or other metal. Photos are developed almost instantly when the underexposed negative image develops on the plate. The metal plates which photos are imprinted on are then coated with dark enamel that can support the photographic emulsion, which is conducted by pouring chemicals directly onto the sheet of metal. It’s a photo studio right in your own hands!

Two tintype printing processes exist: wet and dry. During the wet process, an emulsion must be formed still wet on the plate when exposed to the camera. During the dry process, an emulsion is applied to the plate before use, and can be exposed to the camera when it is already dry. An underexposed image is produced in the emulsion, when the densest areas of the photo correspond with the lightest areas of the actual subject.

Resurgence of Printing on Aluminum

Since modern society has become fascinated with a variety of ‘old-timey’ technology, there has been a resurgence for printing on material like aluminum. Portrait photographers especially appreciate the luminescence that tintype adds to a photograph. It also creates a clean, sleek, modern visual that allows a photo to go frameless.

As a photographic lab and printer, Light-Works considers the tintype to be the foundation of our current practice of printing on aluminum. We’re capable of doing much more than primitive photographs: think of it like tintype on steroids.

How Light-Works Elevates Fine Art Photo Printing On Aluminum

Light-Words operates a photographic quality, direct printing process. We employ ink-jetting UV-curable inks directly onto substrates like anodized and milled aluminum stock, as well as aluminum composite material called Dibond. The colors become crisp, saturated, and bright when printed on aluminum. Oftentimes, the whites and very bright parts of the photo don’t show up, allowing the aluminum to become an element of the photographic print.

A critical part of this process is the photo reproduction, which can generally be achieved using a true flatbed press and continuous tone. Our six-color, variable-dot Fujifilm Acuity Select 28 accomplishes this with increased tonal detail and gradations. Correctly bonding the acrylic-based ink to the aluminum surface is crucial to durable, long-lasting artwork. The inkset we use is Sericol’s latest KN formulation combining wide color gamut, superior adhesion, and durability for small and large format print.

Order a Custom Print on Aluminum

Light-Works is known for its fine, art-quality photographic images and retail graphics, yet we also appreciate going back to our roots with “old school” photography to develop fine print reproductions. Our printing work has been used in fine and public art projects and – most recently – decorated over 100 hotel rooms at The Essex in Vermont. For our client, we printed 115 three foot square panels (of .080” anodized aluminum) of culinary photography by Lynn Karlin.

As you might imagine, this printing project looked spectacular. We don’t mean to toot our own horn, but we believe we’ve got the hang of this whole tintype printing thing.